Week 3

in Nairobi and I still haven’t set foot in the heart of the city. Nor

have I been to the Museum. I console myself with the fact that the CBD is

rarely the most interesting part of any city – the quick drive I have done

through the centre of ‘town’, as it is called, revealed the kinds of tall

buildings, busy roads and even glittering casino one might expect in most

cities. Not that I don’t want to explore further - but I have just been

so busy exploring the other parts of Nairobi that I haven’t made it there yet!

Most

of my time so far has been spent walking or driving between interviews, of

which I have had many (but more on that later). One of the best things

about visiting lawyers, NGO workers, UNHCR and government officials is that

their offices – or alternatively, the cafes they suggest we meet in – are all

over Nairobi. I walk when I can – this is still a relative novelty after

being in Jo’burg. Nairobi definitely feels like a calmer safer to walk

around in, though I would still never go out at night. While security

abounds, I am told this is not due to general crime; rather it is largely a

response to the few terrorist bombings carried out in the city by Al-Shabab in

the last year or so. Perhaps I have been in Africa too long, but this

actually makes me feel safer. When it gets too hot I buy fruit salad from

a roadside stall and put up my umbrella as sun protection. When I get too

dusty and sweaty I look for a shopping centre with a Java House or Dormans café

to recuperate. And when the distances are longer, or I am not quite sure

where I am going, I travel with George, my taxi driver.

The

streets in Nairobi’s suburbs are lovely. At the risk of repeating myself,

they are so green! Huge old trees, grass, vines, hedges and

brightly coloured flowers everywhere. Many gardens still display a very

definitely British sensibility – the house just up the road from where I am staying

could be straight out of the Cotswolds. But a lot the greenery is wild

and sprawling, and it’s often hard to believe you are in a city at all.

The state of the roads themselves has the same effect. Many look like the

have not been attended to for decades, and the extent of the potholes, some of

them several feet deep, makes driving in a straight line nearly impossible.

Last

weekend I venture a little further afield, with a visit to Kibera. Even

if you have never heard of Kibera you will probably feel like you have seen it

a hundred times. It is the quintessential image of poor Africa – an inner

city slum full of dust, rubbish, open sewerage, barefoot children, makeshift

homes and a few animals. As well as being the largest slum in Africa, it

is apparently the most studied, owing to the fact that it is so close to the

CBD and UN-HABITAT’s office is nearby. Many of the homes here have

neither running water nor sewerage and unemployment is apparently somewhere

around 40%.

On the

one hand I think it is important to acknowledge and address the level of

poverty that many people in Africa live in. In fact, getting a better

understanding of what life is like under these circumstances is one of the main

reasons I have wanted to come here for so long. I’ve always believed (or

hoped) that if everyone in the world was forced to come face to face with these

realities they would not be allowed to continue. But having now spent

some time here and having visited Kibera, I feel less sure that perpetuating the

image of the poor, helpless Africa is very helpful at all.

Certainly

Kibera is a place of extreme poverty – there are single mothers there who spend

their days offering to wash other women’s clothes for a sum of about 100

shillings – less than a dollar. And there are children who will catch and

suffer from diseases that could be easily prevented or treated in better

conditions. But most of the people I saw during my visit were anything

but passive victims of their surroundings. Kibera is a hive of activity

and a vibrant breeding ground for small businesses and other entrepreneurial

activities. Many of the shanty-type homes in Kibera double as shopfronts,

selling everything from homemade soaps to pre-paid mobile credit to chapatis.

Kibera

is on the list of places to which both the Lonely Planet and Australian

government advise against travel. This is ironic – according to my guide

Frankie (and verified with others I have spoken to since) Kibera is one of the

safest places in Nairobi, due to the local community’s ‘people power’.

‘People power’ is a slightly euphemistic term for describing the fact that

anyone caught stealing in Kibera will be set upon by a group of locals and,

more often than not, killed for their crime. This is apparently a

result of the community’s impatience and frustration with local police and

justice mechanisms. Unsurprisingly, it has vastly reduced the amount of

crime, at least during the day.

The

other thing that struck me about my visit to Kibera is the fact that so much of

Nairobi is not like Kibera. In many ways, it is a booming

city. There are good universities here, a growing economy and lots of

development – those given the opportunity could really make a go of it.

In fact my guide Frankie grew up and still lives in Kibera. He was

sponsored by an NGO to attend school and is now studying towards an accounting

degree at the University of Nairobi – he shows people around his home town as a

part time job to help him through his studies. No doubt, education is

key. That’s why on Friday I plan to return to Kibera and spend the day

volunteering at one of the local primary schools. I might just have to

teach them how to sing Happy Birthday!

|

| One of the lovely suburban roads where I spend my days walking. |

|

| Entrance to the British Institute of East Africa, my Nairobi home. |

|

| Bus stop in Karen, the suburb named after Karen Blixen (Out of Africa) |

|

| Tree signs are one of my favourite features of the African urban landscape. |

|

There is every kind of religion in Kenya - in the morning I wake alternatively

to church bells and the call to prayer at the nearby mosque |

|

Kibera - Africa's largest slum. The apartments behind are being built as part of the

upgrade/development program, but Frankie explained to me that they are unaffordable for most

Kibera residents, costing about $30 a month (between 2 and 6 times the costs of rent in Kibera itself). |

|

| The railway line through Kibera is still used by passenger and freight trains. |

|

This is Modest, who works with women in Kibera to make

jewellery and other handicrafts for sale at Pam's curio shop |

|

| Homemade soaps for sale - these soaps are made by people infected or affected by HIV/AIDS |

|

I now understand why everyone returns from Africa with photos of children - they love having

their photo taken! Kibera Tours, through whom I arranged my visit, have a quite strict photo

policy, only allowing photos at certain stops during the visit. Frankie made an exception

in this case, after the kids begged for me to take their photos! |

|

The kids love being photographed, but they love even

more seeing their images on the camera view screen afterwards. |

|

| I think this little fella saw himself as our mini security guide - here he is chasing off some of the bigger kids. |

|

| The view from inside a Kibera home - the mzungu lady is an intriguing sight in Kibera.. |

|

| Women doing their washing together at a community water source. |

|

Almost every second wall or fence in Kibera has an NGO's logo on it. There are

apparently over 800 NGOs working in this area, only some of the working well. |

|

| The Bead Factory. This factory buys cow, goat and camel bones from butchers and slaughterhouses and turns them into jewellery. It's a remarkable use of limited resources, though the dust and smell of bones is a bit overwhelming! |

|

| It's not only the kids who love having their photo taken! |

|

What would Workcover say about this.... The head of the factory proudly showed me the scars

on his hand, suggesting they are some kind of mark of achievement for workers. I'm not so sure...

This worker is making little turtle shapes from the bone - you can see a pile forming on the floor. |

|

| And this is the end result! |

|

| Toi Market - this market is all that separates Kibera from one of Nairobi's expensive, middle-class suburbs/ |

|

| Toi Market |

|

| Coal is sold here for about ten cents a bucket. It will be used for heating and cooking. |

|

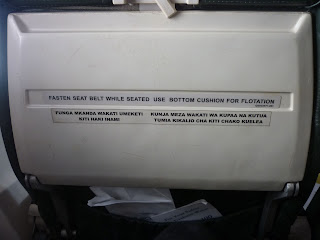

| I don't know about you, but this sign somehow just doesn't inspire confidence in me.... |

|

Most of the dogs I see or hear in Nairobi are guard dogs. Judging by

this fella's wagging tail, he is not very good at his job. |

|

| The road home to my guesthouse at the end of the day... |