A refugee camp is a very difficult place to

get in to if you are not a refugee. The

preparations for my visit to Kakuma Refugee Camp, in Kenya’s northeast and

about 90 kms from the South Sudan border, began long before I even left Sydney and

required numerous approvals and logistical arrangements. First there was the special permission

required by my university, owing to Kakuma being located in a current DFAT ‘do

not travel’ area, then the approval of Kenya’s Commissioner for Refugees then

UNHCR had to agree to host me, find me accommodation and a seat on the charter

flight between Nairobi and Kakuma’s small airstrip.

In fact I think these extensive controls

are entirely reasonable – there is enough to deal with at a refugee camp

without having to worry about itinerant researchers, journalists or

tourist. All of these controls are aimed

at ensuring that anyone who visits Kakuma does so with at least the intention

to make a contribution to the refugees who live there (except for the special

permission of my uni, that was about insurance).

Kakuma Refugee Camp is one of Kenya’s two

main refugee camps. The other – Dadaab –

is in the country’s east, near Somalia.

The current security situation there, which is quite unstable and has

meant that refugee registration and status determination is not currently

taking place, led me to decide fairly early on not to visit. Kakuma, by contrast, is fairly peaceful. Armed with my various travel approvals, a

small bag, a new hat and lots of sunscreen (in Kakuma it gets up to 47 degrees)

I arrived at Nairobi’s Wilson Airport at 5.45 am Monday morning for my very

first UN Chater Flight (I’d be lying if I said I wasn’t a bit excited).

Check in turned out to be one of the

interesting experiences of my entire week in Kakuma. I had carefully made sure to pack light and

avoid any obvious signs of Western wealth.

I left behind my ipod, jewellery and safari lodge cap – this time less

because of security, and more because it seemed rather inappropriate to wander

around a refugee camp bearing souvenirs from a comparatively luxury

holiday. So I was staggered to watch one

of my co-passengers checking in a huge, flat screen TV. Really?

You’re taking a flat screen TV to a refugee camp?? As I wondered to

myself about just exactly who I was sharing my flight to Kakuma with I struck

up conversation with the small party sitting next to me in the waiting

area. They introduced themselves as

evangelical Christians from the US visiting Kakuma to see the work their church

was doing there. I wondered how well the bureaucratic controls were really working.

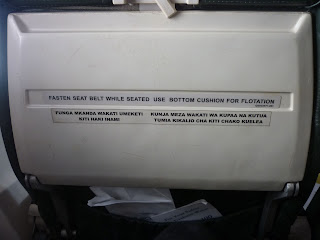

The flight itself, on a small, relatively

low-flying plane, gave a great view of the northern parts of Kenya. As we travelled north-west from Nairobi the

land got drier and rockier (the air hostess had told us that if we crashed we

could use our seat cushions as flotation devices, though I can’t imagine where)

until we started our descent to Kakuma itself.

The view from the plane is the view of the

refugee camp that everyone knows.

Sprawling tents and shacks surrounded by barren, dusty desert. What struck me most was not the camp itself –

which looked quite established and organized – but the dilapidated dwellings

made from branches, plastic and assorted rubbish, on the camp’s outskirts. I thought to myself what a harsh life it must

be for those who travel the many hundreds of miles, sometimes by foot, to

refugee camps like Kakuma only to not be let in, either because the camp is

full or because of delays in registration.

I later learned, however, that the dwellings I saw looking at are in

fact the homes of the locals – the people of the Turkana tribe, who live and

herd their cattle and goats on the land surrounding Kakuma refugee camp.

When we touched down on the red, gravelly

air strip, goats ran past, a man on a bike stopped and stared, and the kids

playing soccer in the dust ran to the wire fence surrounding the strip to peer

at the new arrivals, as we disembarked and collected our bags (and TVs) from

the rear of the plane. While the

evangelicals hopped into one of the many NGO jeeps waiting beside the airstrip,

I joined the UNHCR staff and pilots on the UN mini-bus and headed off to check

in to my lodgings for the week, inside the UNHCR compound.

|

| Check in - Nairobi Wilson Airport |

|

| Airline safety, UN style |

|

| Aerial view of Kakuma Refugee Camp. |

|

| View of the air strip after landing. |

|

| Entrance to Kakuma 3 - the third and most recent section of the camp. |

|

| Every NGO you can imagine has a sign in Kakuma - unfortunately I'm not sure it necessarily means they are doing much there. |

|

| Arrival at the UNHCR compound. |